Introduction

Modern theorem provers and optimizing compilers are built on an interesting concept: the ability to recognize when two things are equal, even if they look completely different. It’s not enough to just match the syntax - we need to match the semantics as well. That’s where E-Matching comes in.

What is E-Matching?

E-Matching is a pattern matching technique that considers syntactic structures and established equalities. Suppose you’re trying to apply the axiom:

The solver must find terms in its database that match f(x). These need to match syntactically, and up to equality. The “E” in E-matching refers to equality reasoning, usually captured using “E-Graphs” or congruence closures.

Why it’s usually associated with SMT solvers

E-matching comes from the world of SMT Solvers, where it’s used to instantiate quantified axioms during the proof search. The general setup is: the solver knows a bunch of constraints and terms, and it’s trying to apply some universal quantified formulas, such as ∀x. f(x) = x. To do this effectively, it needs to search for instances of f(x) inside a big heap of terms - but doing so modulo equality.

In solvers like Z3, E-matching is key to making quantifiers tractable. Without it, you’d have to blindly try substitutions or generate ground instances randomly - both of which scale terribly, for the obvious reasons. E-matching provides a middle ground: a way to find promising instantiations by searching through terms that already exist in the solver’s database.

What is an E-Graph?

Understanding E-Graphs is important to grasping the application of E-Matching in Superoptimization and understanding the next sections. I recommend reading this blog on the subject.

The basic idea is quite simple, we have 3 important things to understand.

E-Nodes - These represent individual expressions or operations, such as addition or multiplication, within the graph. They sometimes have operands, such as the left and right-hand sides of an addition, and it results in some value or “dependency”.

E-Class - E-Classes group the aforementioned E-Nodes that are semantically equivalent, allowing interchangeable use in transformations. E-Nodes have edges to E-Classes, and due to this equivalence invariance, a node can choose any other node inside the operand E-Class, and the semantics will be guaranteed to be the same.

E-Graph - A directed graph (note that it’s not acyclic, this is important for certain rewrite rules, which can be applied to their result), which contains some number of E-Classes.

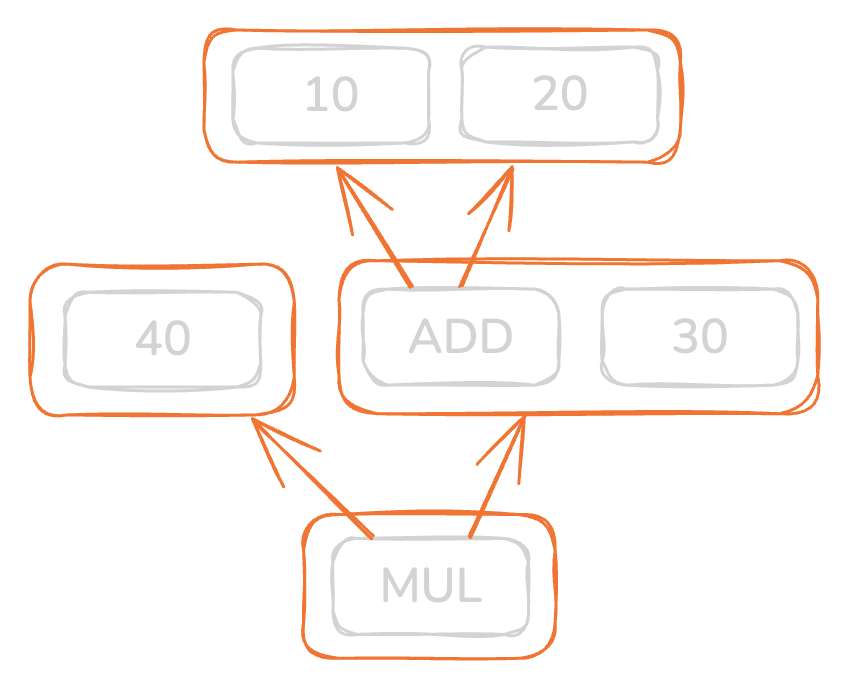

The E-Graph comprises six nodes: the constants 10, 20, 30, 40, and the operations mul and add. The orange boxes denote E-Classes, each containing semantically equivalent nodes. You should note that the nodes add and mul have edges that are pointing to other orange boxes, not other nodes.

Through peephole optimizations, such as constant folding, we’re able to prove that 10 + 20 is equal to 30. After this relationship is found, we can perform a “union” on the two classes, containing 30 and the 10 + 20 nodes, merging them into one.

Afterwards, the mul node will result in the same value, no matter if it looks like (10 + 20) * 40 or 30 * 40.

Note that this isn’t a new idea, and optimizing compilers such as cranelift use E-Graphs as a middle-IR in their optimization pipeline.

Using E-Matching in Superoptimization

I first came across this idea while building an optimizing compiler using the previously explained E-Graphs, called Zob.

Zob’s goal is to find semantically equivalent but cheaper representations of its IR by applying rewrite rules. While there are additional, more complex optimization passes, rewrite rules form the core of the optimizer. These rewrites range from simple peephole optimizations, such as x * 1 → x or x + 0 → x, to more advanced transformations involving bit manipulation or algebraic factoring.

The challenge is familiar: for each rewrite rule, we need to find sub-terms in the E-Graph that match the rule’s left-hand side, modulo equality. Since the E-Graph can contain tens of thousands of nodes, doing this efficiently becomes nontrivial.

This brings us to the core question:

How can we find matching patterns in an E-Graph efficiently, without wasting time on redundant or irrelevant paths?

The paper Efficient E-matching for SMT Solvers gives a remarkably elegant and practical answer - one that can be transplanted into the optimization world.

The rest of this post breaks down that algorithm, why it matters, and how I adapted it in Zob to work with E-Graphs.

Naive Matching and Its Limits

Let’s take a step back and look at the more obvious, naive approach. While it’s inefficient, it helps build a solid foundation for understanding the problem.

For reference, you can find the old naive implementation in Zob here - though it’s since been removed and replaced with the better one.

Consider this simple rewrite rule:

Let’s break down the left-hand side of the rewrite rule.

The multiplication (·) is the “root” of the expression. Written as an S-expression, it becomes

(* x 1), which makes the structure more clear.The

xis a variable or binding. It is a placeholder that can match with anything, as long as the usages of the variable are consistent. In the E-Graph, we can ensure that all usages ofxare equal by requiring them to belong to the same E-Class.The

1is a constant. Constants are canonical nodes in the E-Graph: each E-Class can contain only one. If two constants are equal, they are the same E-Node and are placed in the same E-Class.

The naive matching algorithm might look something like this (in magical Zig-esque pseudo-code):

/// Returns true if `pattern` matched with the node in the E-Graph, `false` otherwise.

fn search(node: Node, pattern: Pattern) bool {

if (pattern.root == node) {

for (node.operands(), pattern.operands()) |child, sub_pattern| {

const result = searchClass(child, sub_pattern);

if (!result) return false;

}

return true;

}

return false;

}

fn searchClass(class: Class, pattern: Pattern) bool {

for (class.nodes) |node| {

if (search(node, pattern)) return true;

}

return false;

}

We’d then run this search function over every node in the E-Graph, collecting matches. But this approach is wildly inefficient. It wastes time exploring paths that are irrelevant or already explored. The bottleneck comes from the depth of the pattern and the number of variables it contains.

The time complexity is roughly: , where:

mis the total number of E-Nodes.|E|is the average number of E-Nodes per E-Class.kis the number of variables in the pattern.

Where a Query Compiler Shines

In the naive approach, we try every possible way to bind the pattern to the E-Graph - recursively exploring pattern applications, checking equalities, and backtracing when a path doesn’t work out. The search space can be enormous, especially when matching deep patterns or working with larger E-Graphs.

To address this, de Moura proposes a much faster approach: compile the pattern into a virtual machine program and run that over the E-Graph. The key insight I find most interesting is to treat pattern matching as a join-like query over a relational structure - an approach that enables systematic pruning, reuse, and a sort of incremental compilation.

This “query compiler” transforms a pattern into a set of instructions that explicitly guide the search, replacing recursive traversal with a well-structured program. But for this to work, two core ideas are needed:

- A fast way to pre-filter candidate terms that might match a given pattern structure.

- A mechanism to reason about equality when terms that look different are actually equivalent.

These problems are solved using discrimination trees and congruence closure, respectively.

Using Discrimination Trees to Index Patterns

One of the main bottlenecks in the naive matching is scanning through huge E-Classes to find terms that match the shape of a subpattern - e.g. locating all f(...) nodes in a class. Instead of repeatedly scanning through these terms, the query compiler builds a data structure called a discrimination tree.

Discrimination trees are trie-like structures that index terms by their syntactic shape. That means function heads and their arities are used to organize terms in a tree, allowing for fast retrieval of all terms that could possibly match a given subpattern, and sorting them by the most likely candidates.

Think of this as a pre-filtering step -the discrimination tree tells you: “Here are all the terms that structurally match f(x, y)”, even before considering any equalities.

What is a Congruence Closure?

But what about the cases where different-looking terms are equal?

For example, suppose an E-Graph knows that:

By the rules of congruence, it should also know:

This kind of reasoning is captured by congruence closure - the process of taking known equalities and deriving additional ones that follow structurally.

Formally:

In plain terms: equal things stay equal when placed in the same context. If two arguments are equal, then the function applications built from them are equal too.

This is exactly the principle behind E-Graphs: equal terms belong in the same E-Class, and congruence closure keeps the equivalence information up-to-date.

Combining with Congruence Closure to Match Modulo Equality

Combining these two ideas enables efficient matching modulo equality. When pattern matching over an E-Graph, you’re not just checking whether a variable can bind to a single term - you’re asking whether it can bind to any equivalent term in an E-Class.

This matching process can be understood as a relational join over:

- The children of E-Nodes in the E-Graph.

- The constraints imposed by the pattern’s structure.

- The equivalence is maintained by congruence closures.

The join-based view allows you to:

- Avoid revisiting equivalent matches.

- Find all bindings that satisfy the pattern up to equality.

- Share work across overlapping patterns.

This design lays the groundwork for more advanced ideas, like multipatterns, which allow you to match several patterns at once and share computations - though we won’t cover that in this post.

The upshot: what was once an exponential recursive traversal can now be executed efficiently as a flat program — thanks to compiled queries, structural indexing, and congruence-aware reasoning.

Using it in E-Graphs

To put this compiled-matching idea into practice, we need to take a detour into the virtual machine described in the paper.

The E-Matching Virtual Machine

The paper proposes a simple but powerful virtual machine that executes a custom bytecode for pattern matching. Each pattern is compiled into a sequence of instructions that manipulate the abstract machine state - registers, continuations, and a backtracking stack.

Here’s the instruction set from the paper:

init(f, next)- Start matching the root of the pattern.bind(i, f, o, next)- Enumerate all function applications inreg[i]that match the pattern headf.check(i, t, next)- Check thatreg[i]equals a constant termt, modulo equality.compare(i, j, next)- Check that two registers point to equal terms (i.e., same E-Class).choose(alt, next)- Push an alternate branch to the backtrace stack.yield(i, ..., iₖ)- Emit a successful match (substitution).backtrace()- Pop the next continuation from the backtrace.choose_app(o, next, s, j)- Used insidebindto iterate through candidate termsf(...).

Ours will look a bit different. There are two main instructions:

bind(f, i, o)- Enumerate all function applications inreg[i]that match the pattern headf.compare(i, j)- Compares whetherreg[i]andreg[j]are equivalent (the same E-Class).

There are also instructions like lookup and scan, but those are used for optimization and multipatterns, which we won’t cover here.

Note, you can find the whole implementation here. My design is heavily inspired by the implementation in egg, I recommend checking out that library; it’s a treasure trove of interesting ideas.

Walkthrough

Now let’s walk through an example. We have an E-Graph that looks like this:

(add (mul 10 20) 30)

No need to point out the E-Classes here, since there are no two equivalent nodes.

We want to search for all instances of the pattern (mul x 20).

Step 1. Initialize the compiler with our pattern.

fn addTodo(

c: *Compiler,

allocator: std.mem.Allocator,

pattern: SExpr,

id: SExpr.Index,

reg: Reg,

) !void {

const node = pattern.get(id);

switch (node) {

... // Removed for brevity.

.node,

.constant,

=> try c.todo_nodes.put(allocator, .{ id, reg }, node),

}

}

The node variable here will be the root of the pattern, or in our case just the entire pattern, since it’s so simple. Operators such as mul have the node tag, so we put it on the todo_nodes array-hashmap, along with reg which will be the register associated with the class containing the mul node.

Step 2. Emit instructions

Now that we have that basic setup done (trust me, it gets a lot more complicated for larger patterns), we need to compile our query.

We have an iterator that runs and gets the next query to compile. The main logic for it is here, and the goal is just to sort the possible terms known to the compiler and find the closest one. By doing this pre-filtering process, we’re lining up the instructions to be emitted in a way that should, in theory, be more optimal and time-efficient.

Now that we have the next term, we can issue the instruction,

try c.instructions.append(allocator, .{ .bind = .{

.node = node,

.i = reg,

.out = out,

} });

for (node.operands(), 0..) |child, i| {

try c.addTodo(

allocator,

pattern,

child,

@enumFromInt(@intFromEnum(out) + i),

);

}

The node variable is the pattern head that was mentioned before and reg is the E-Class that we want to search through to find possible syntactic matches. Afterwards, we iterate through the operands of the pattern, so for our example that would be the variable x and the constant 20, and add them to the queue to be picked out in the next iterations. You’ll notice that constants are handled in the same way that nodes are in the addTodo function above.

Variables are handled a bit differently. They don’t need to match with anything except other usages of the same binding. Remember that when there’s more than one of the same variable in a pattern, they must be equivalent, or else the pattern fails to match.

Consider the example (mul (div_exact ?x ?y) ?y). This is a common peephole to remove duplicate multiplications and divisions (in cases where they divide without a remainder), and it only works if ?x is being divided and multiplied by the same thing.

Because in our example, there’s only one ?x binding, we don’t need to compare it against anything else. If it did appear a second time the following code would have been triggered:

if (c.v2r.get(v)) |j| {

try c.instructions.append(allocator, .{ .compare = .{

.i = reg,

.j = j,

} });

}

Where v is the variable name. The compare instruction makes sure that during the execution, the E-Classes referred to by the j and reg registers are equal (or in our case, the same E-Class).

The implementation of the compare instruction is incredibly simple:

.compare => |compare| {

const a = m.registers.items[@intFromEnum(compare.i)];

const b = m.registers.items[@intFromEnum(compare.j)];

if (oir.union_find.find(a) != oir.union_find.find(b)) {

return; // no match

}

},

So our final query for the example above looks like:

{ bind((mul %0, %1), $0), bind(20, $2) }

(Removed the out register from the bind instructions, since it isn’t relevant to explaining this.)

In the first instruction, we bind the register $0 to the mul node, only if they syntactically match. If that ends up happening, we will run the second instruction and try to bind the $2 register to the constant 20. If that also matches, then we have completed the search, and a match has been found!

Conclusion

In this post, we explored the core ideas behind E-Graphs - what they are, why they’re useful, and how enable reasoning over equivalence. We explained the basic ideas required to understand the abstract matching machine, such as discrimination trees and congruence closures.

We explained the basic ideas behind E-Graphs, and why such a data structure is even useful. We looked at how these ideas come together in the query compiler described by de Moura.

Finally, we walked through a minimal implementation of this approach for an E-Graph based optimizing compiler, showing how a couple of well-chosen instructions can replace the need for recursive tree walks and brute-force matching.

This only scratches the surface - we may explore more in future posts and dive into advanced topics like multipattern matching, backtracing strategies, and how the E-Graph extraction process works.

I hope this post gave you a clearer picture of how matching can be practical when backed by the right ideas.